Sir Howard Colvin, in his Unbuilt Oxford (1983), devotes an entire chapter to Magdalen entitled ‘Indecision at Magdalen’ in which he characterizes the two centuries of building programmes at the College from the 1720s as “an epic of architectural mismanagement.” There was great appetite within College to improve, or remove, its Gothic buildings and to expand the range of accommodation as a number of other Oxford colleges were doing the same. Drawings from 1724 by Nicholas Hawksmoor were some of the earliest re-imaginings of Magdalen and left nothing of the original set of buildings but the Great Tower.

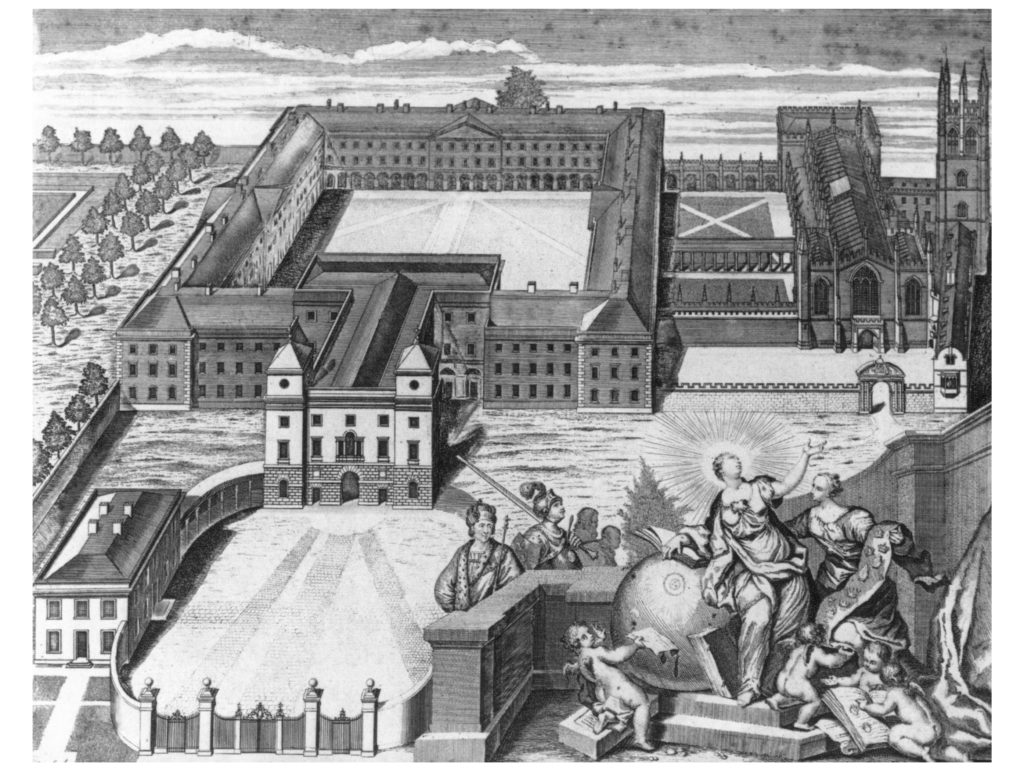

Engraving of Edward Holdsworth’s plans for the complete re-design of Magdalen College, viewed from the west (i.e. Longwall Street), Magdalen Collge Library

The most ambitious plans commissioned for Magdalen, though, where those of one of our own Demies – Edward Holdsworth (D. 1705-1715, B.A. 1708, M.A. 1711) – who submitted drawings to President Edward Butler in 1729. The above engraving shows Holdsworth’s designs as viewed from the west, where a new entrance to the College would have been provided via an oval forecourt and a grand ‘T’ shaped library; the sole surviving remnants of the Gothic college were to be the Great Tower and the Chapel and Hall and the external ground level facades of Cloisters, with the rest to be taken down to provide a linking structure to the new Great Quadrangle. Work was planned in phases and by 1734 the north range of the new quad was finished with its ends left rough to link the east and west ranges. However, College politics and finances stopped the rest of the works and this range, now known as New Building (below), is the only remnant of Holdsworth’s great plan.

Following the construction of the New Building in 1734, College sought the advice from a number of architects to rejuvenate the site. Amongst those consulted, James Wyatt (the great ‘Gothiciser’) provided his radical ideas of tearing down Cloisters and cladding New Building in a Gothic face in the late 1790s. John Nash and renowned landscape architect Humphry Repton were engaged by College in 1801 to offer their own views. Repton, who had provided plans for dozens of country estates and parks at the end of the 18th century, produced one of his most elaborate ‘Red Books’ with his son John Adley Repton for the College to consider.

Detail from Humphry Repton’s plans for the Water Meadow of Magdalen College, Magdalen College Archives MC:FA16/4/1AD/1

Repton’s ‘Red Books’ were famous for the lift-up flaps which showed a landscape or subject as a before-and-after, allowing the reader to familiarise themselves with a view or a building before having Repton’s plans revealed to them. For Magdalen, his book includes a lengthy introduction to the architectural history of the site, six views of the College site, as well as a new schematic drawing of the site and smaller figurative sketches.

Detail from Humphry Repton’s plans for the New Building of Magdalen College, Magdalen College Archives MC:FA16/4/1AD/1

Repton’s plans were, to say the least, quite radical. He proposed the flooding of Water Meadow, turning it into a pleasure lake for boating and fishing; he took the ideas of Nash and Wyatt and proposed creating a three-sided quad with New Building to the north and the north wing of Cloisters replaced (and this space removed!) facing his new lake; the whole of which was to be cladded in a new Gothic face to better blend the old and new of College.

Needless to say, Repton’s vision of the College as a Neo-Gothic paradise was never fulfilled. The 1820s saw modest refurbishment to most of Cloisters, including the extension of the Old Library and the construction of the Oriel Window.

Although it may be thought that the era of sweeping changes to College buildings had long passed by in the 20th century, the tale of Magdalen re-imaged has one final twist.

In the 1940s the then President of the College, Sir Henry Tizard, was considering plans to re-decorate the President’s Lodgings and engaged the architect Oliver Hill to draw up some designs. At the same time Hill was designing the plans for the Lodgings, there was discussion in Magdalen about a larger architectural project for a new set of buildings by the Botanic Garden. In 1953, the lease of the Botanic Garden to the University was due to expire and the Plant Sciences department (then “Botany Department”) took the decision to vacate its buildings that sat between the Garden and High Street and moved to the newer science area on South Parks Road. The freeing up of these buildings and the need for more space for student accommodation therefore gave College the opportunity for change.

Aerial perspective from the north of a design for a pair of new buildings on the High Street frontage of the Botanic Garden by J.D.M. Harvey for Oliver Hill (1946), Magdalen College Archives MC:FA19/3/1AD/5

Hill, who had been struggling to revive the success of his architectural firm after the war, saw this as the perfect opportunity to showcase his work. Under his own initiative, unpaid by the College, and unbeknownst to the majority of the Fellowship (with the exception of President Tizard), he began to develop his new plans. The painting above show Hills’s plans which involved demolishing all buildings either side of the Danby Gate and erecting a classically designed crescent shaped building. This plan would have provided 84 sets of rooms for students and a transparent colonnade at its base so the Botanic Garden could be viewed from High Street. He developed plans and even a model to showcase his design; one of his drawings of this plan was exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer exhibition in 1947 followed by an article in Country Life. However, unfortunately for Hill, this is as far as the plans went. One of the chief proponents of the project, President Tizard, stepped down in 1946 and the plans displayed at the summer exhibition and in Country Life caused outrage amongst many of the Fellows who were hearing about these plans for the first time.

In the end Hill’s plans were not accepted for the Lodgings or the redevelopment by the Botanic Garden. However, for the College the demand for undergraduate accommodation was still unmet and in the 1960s the Waynflete building was erected across the Cherwell on the other side of Magdalen Bridge.