Long before William Orchard, Waynflete’s architect, began to lay out the plans for the Cloister of Magdalen College, this site would have been an attractive place for Britain’s wild beasts living along the Thames Valley. A variety of mammals – roe deer, otters, badgers, and foxes, among others, can still be seen along Oxford’s waterways. During the last Ice Age, however, the largest and most impressive beast to be found in Britain was the mammoth – a relative of the modern elephant.

The mammoth flourished during the last ice age, adapted for the colder weather than the modern elephant and featuring its famous “woolly” coat. Originally thought to have disappeared from Britain about 21,000 years ago, recent evidence has suggested the mammoths recolonized Britain after that time, persisting for another 7,000 years. Various species of mammoth remains have been found throughout the northern hemisphere up until the very end of the Ice Age, 10,000 years ago. With temperatures warming, the mammoths became extinct, the last dying off in Britain by 14,000 years ago. On tiny Wrangel Island off eastern Siberia, the very last redoubt of mammoths, a group of about 500 individuals, continued to survive well into recorded human history, finally succumbing to the changing climate in 1650 BC, when Egypt’s pyramids were already about 1000 years old.

The mammoth flourished during the last ice age, adapted for the colder weather than the modern elephant and featuring its famous “woolly” coat. Originally thought to have disappeared from Britain about 21,000 years ago, recent evidence has suggested the mammoths recolonized Britain after that time, persisting for another 7,000 years. Various species of mammoth remains have been found throughout the northern hemisphere up until the very end of the Ice Age, 10,000 years ago. With temperatures warming, the mammoths became extinct, the last dying off in Britain by 14,000 years ago. On tiny Wrangel Island off eastern Siberia, the very last redoubt of mammoths, a group of about 500 individuals, continued to survive well into recorded human history, finally succumbing to the changing climate in 1650 BC, when Egypt’s pyramids were already about 1000 years old.

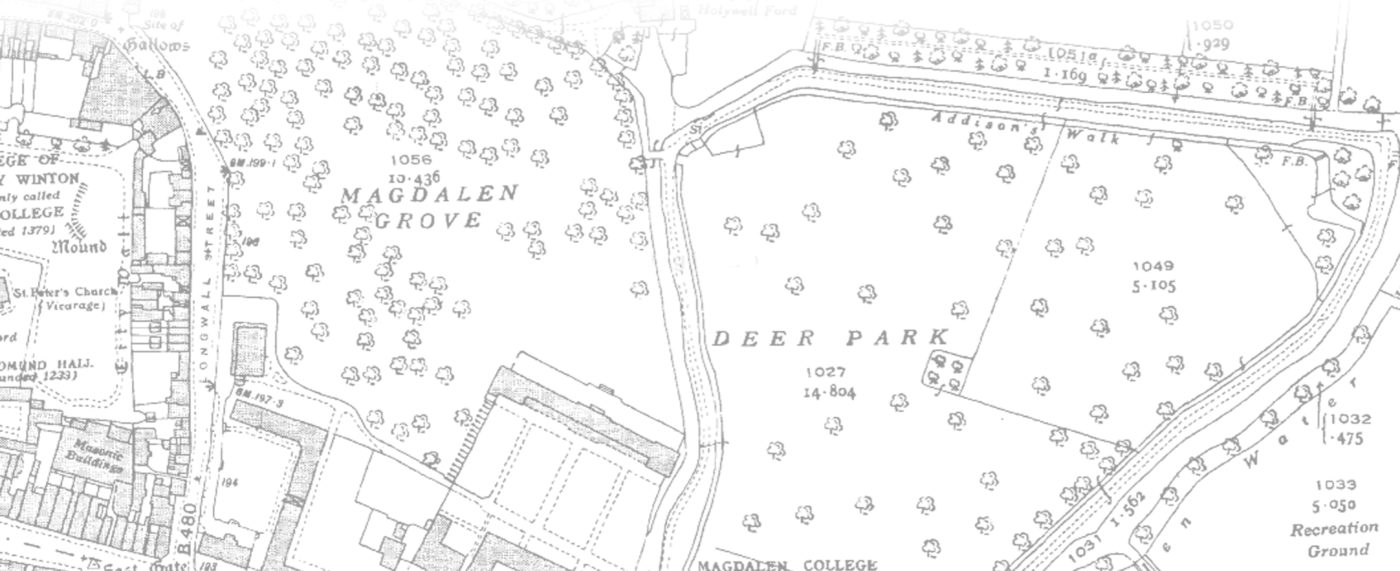

The safe, riverside valley site that is now Magdalen’s Grove would likely have hosted a number of these creatures in the aeons preceding the College’s foundation, but we have evidence for only one. In 1922 workmen were engaged in the College to reclaim stone masonry from a watering hole that had been built for the College deer. The trials of the Great War had rendered materials scarce, and it was decided that the stonework was a bit too fine for the deer and would be of greater value elsewhere. During the demolition, one of the workmen spotted what appeared to be ivory amid the masonry, and recognizing this as likely more valuable still than the stone, alerted the Fellows, including R. T. Gunther, Tutor in Natural Sciences at the time.

Fragmentary remains of a mammoth tusk discovered in Magdalen College Grove in 1922, conserved in plaster of Paris R.T. Gunther, M.A. and Fellow of Magdalen College.

The reclamation project turned swiftly into an excavation project, seeking to recover as much of the mammoth as possible (Mammuthus primigenius). A nearly complete tusk was found, measuring over six feet in length and 17cm in diameter, but about half of it was too crumbled and decayed to be removed intact. The other half was reinforced with plaster of Paris and successfully removed and preserved, here, along with six molar teeth. The same site continued to produce ancient bones (sadly with much of the rest of the mammoth inexpertly destroyed in the process), including several mammoth molars. In 2009, studies found that the tusk dated from the second inter-glacial period, about 240,000 years ago.

Detail of the lower jaw of “Ursus anglicus” named by R.T. Gunther – the fossil was discovered in 1922 on the grounds of Magdalen College. Holotype cast now OUMNH Q.2705/p

The first fossilised bear to be found in Oxford followed soon thereafter. Gunther’s own account of the discovery and excavation of these remains can be found in the Daubeny Laboratory Register. Gunther writes:

“I immediately went out … [and] found a pile of fragments of bones of Bos, Cervus, Mammoth, including parts of two lower jaws and teeth, and on top of all a beautifully preserved ramus, in two pieces, of the lower jaw of a bear. This was the first occasion that the remains of a fossil bear had been found in Oxfordshire. … I came to the conclusion that it resembled the so-called U. horribilis from the Lower Pleistocene … It seemed well, therefore, to make a new species of British Bears … To this name Ursus anglicus was given, and the Magdalen College jaw is taken as the type.”

Gunther published a full study of the newly-named Ursus anglicus in 1923 in Annals and Magazine of Natural History XLVIII. He deposited the holoytpye cast of the Ursus anglicus, as well as other remains with the University’s Natural History Museum shortly after recovery, some of which can be seen below.