The monastic life originally intended for the Fellows by Waynflete’s statutes did not permit frivolous distractions. Consequently, Waynflete placed various restrictions on all matter of sport and hobbies in which Fellows might have otherwise indulged. Animals were no exception, with hounds and other dogs, songbirds, hawks, and ferrets all forbidden. This includes both animals that would have been used for sport, such as hounds and hawks, as well as those pets which might have constituted a distracting hobby that could undermine the focused, clean life envisioned for the Fellowship.

There is nothing perhaps so well known about the College as its deer. The Magdalen deer herd, which lives primarily in the Grove, and summers in the Water Meadow, has been present on sight since around 1700, when college records first begin to reflect the costs of deer keeping, with entries for food, feeding troughs, and other equipment. The herd are the only such large-scale husbandry operation still maintained by an Oxford college.

The 18th century deer herd would not have had the free run of the Grove given to their modern descendants. Much of that area was still taken with orchards, bowling greens, formal gardens, stables, and other outbuildings. The current herd has the Grove to themselves, and are also allowed to graze the Water Meadow, bounded by Addison’s walk, in the late summer. This procedure serves to maintain the health of the College’s population of rare snake’s-head fritillaries, which require regular grazing to continue to flourish.

Over the course of the following century, the Grove was established as unified parklands, and the herd given free reign of the space. This edition of the Oxford Almanac, depicting the north face of the New Buildings in 1787, shows how much had changed since the beginning of the century. The Grove had, by then, taken on its present arrangement occupying the entire northern half of the college’s main site, and had been styled in an artful approximation of a wild meadow. The New Buildings, the first range of what was originally planned to be an enclosed Palladian quadrangle have already been erected, with their north side appearing largely as it does today.

Many will have noticed our new white stag in the Grove in recent years; adding new blood to the herd is important in maintaining the animals’ genetic health. This white stag was one of two added for this reason in 2018. In this case, the colour was carefully chosen to effect the overall colouration of our herd. Fallow deer come in four colour morphs: common (having a mid-brown coat, with a darker coat in winter), melanistic (dark throughout the year), leucistic (white, but not albino), and menil (light brown with white spots). The common morph is of course the most numerous, while Leucistic and melanistic deer are rare, and menil not too uncommon. In recent years, due to the randomness of breeding, our deer, traditionally of the spotted menil variety, have tended toward standard and melanistic coats, lacking spots and darkening in colour. This rare white stag, along with another menil one, have been added to restore some of the white and menil genes lost recently.

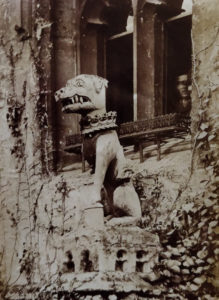

A photograph of the deer ‘hieroglyph’ in The Cloisters of Magdalen College, Magdalen College Archives MC:F22/P9/2

The Deer Herd Book Society of Great Britain released regular records of the managed herds in the UK, documenting age and composition of each. This 1932 edition includes Magdalen’s herd, then composed of about 20 deer. The record erroneously suggests that the herd had been established for 130 years. Given that records of the deer begin in the early 18th century, this record misses out nearly 100 years of deer keeping at Magdalen!

Deer can also be found in other parts of College, including the medieval fabric. This photograph depicts one of the statues that top each buttress surrounding the North, East, and West ranges of the College cloister, known as the Hieroglyphs. Though it bears rather little resemblance to the deer in our herd, it does depict a deer, its neck surrounded by a crown. Despite its ferocious appearance, the deer is meant to represent peace, and an unwillingness to fight unless provoked.

The College’s extensive gardens have played host to a long history of creative plantings, offering a respite from the city which surrounds its walls. Magdalen’s gardens have also maintained a unique focus on decorative animals in addition to the plantings, with a variety of ornamental species having inhabited the College. Attempts have been made to raise Australian black swans on the Cherwell, and for about one year several peacocks were introduced to the Grove, only to be removed by the Bursar because of the disruption caused by their famously loud cries. An offer by an American alumnus to donate several ostriches was, regrettably, declined.

The College’s refusal to accept the gift of ostriches for the gardens was evidently informed by their experience with a pair of emus which had been sent to inhabit the Grove in the late 19th century. One of the large birds died in transit, but the other was successfully introduced to the gardens and became a firm favourite with the students and visitors. The emu did not last, however, and died within a year. The above obituary avers that the cause of death was unknown, but R. T. Gunther, in his History of the Daubeny Laboratory at Magdalen College, suggests that it succumbed to heart failure, having been over-fattened on currant cake by its many admirers. The skeleton of the bird was given over to the Daubeny Laboratory, where it served to illustrate the unusual anatomy of the ratites, the group of large flightless birds including ostriches, emus, and rheas.

The College Statutes has had specific clauses outlining the banned animals from the foundation of the College in 1458: “In like manner, We enact, ordain, and will, that no one of the Scholars or Fellows of the said College do keep a harrier, or other hound of any kind, or ferrets, or a sparrow-hawk, or any other fowling bird, or a mavis or any other song bird”. The text goes on to ban dice and card games, with all these proscriptions made in the name of preserving the reputation of the College.

Despite Waynflete’s ban, a number of dogs have been kept in the College, both as pets and for sport. This copy of the Oxford Almanack from 1778 shows several Fellows with their dogs in the Cloisters. President Routh kept a famous dog that had allegedly been orphaned and raised by a cat, and adopted its mother’s mannerisms. Many of the Fellow’s referred to this dog as “Routh’s cat” – perhaps a convenient legal fiction given that cats are not banned in the Statutes.

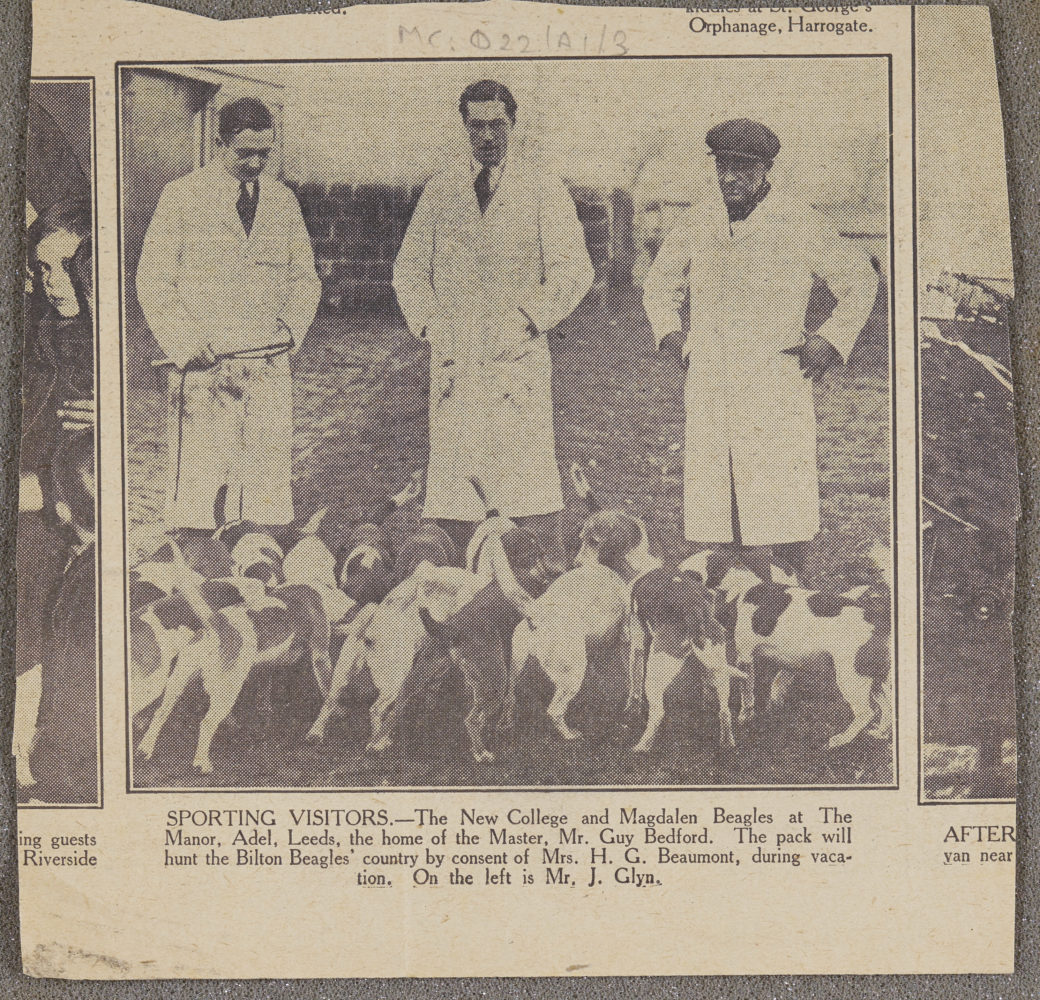

The New College and Magdalen Beagles in 1920, preparing for a hunt near Leeds. Magdalen College Archives MC:P402/P1/3

The College also flouted, in rather an organised and official way, the ban on dogs for sport. The New College and Magdalen Beagles were maintained between the two Winchester colleges (New College having been founded by an earlier Bishop of Winchester, William of Wykeham). Beagling involves the hunting of rabbits and hares on foot, with trained beagles, and was often one’s introduction to hunting with hounds before moving on to the more challenging fox hunt. The New College and Magdalen Beagles have since merged with another local pack, but their genetic contribution lives on.

This report, submitted to the club’s committee, recounts the outing of the beagles to Leeds. The weather did not hold, and the pack underperformed, catching only six hares across several days.

The beagles were a popular diversion for members of the College, including the Prince of Wales, later to become the ill-fated King Edward VIII, shown here.

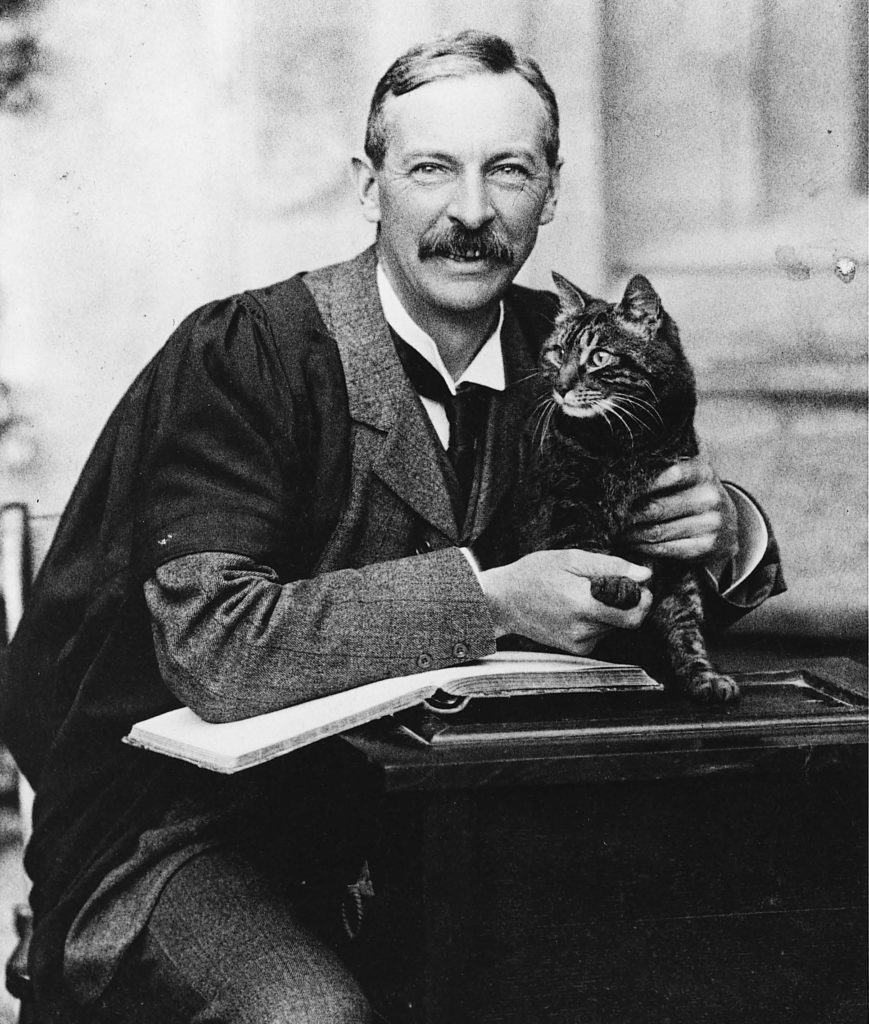

Dr. Tim (The cat) with C.R.L. Fletcher, Fellow in Modern History. Magdalen College Archives MC:O1/P1/1

Unlike so many animals, cats are not banned in the Statutes, though no reason for this omission is given. It is possible that cats, being useless for sport and requiring very little active attention when kept as pets, were seen as less distracting and corrupting than other potential pets. More likely, cats were thought of as an important working animal, at least at first. Magdalen will have long played host to a variety of vermin, and a mousing cat would have been one of the College’s many employees – a tradition still maintained at other Oxford colleges, and in 10 Downing Street! Though no official College cat is currently employed at Magdalen, several have served in the past, including Dr. Tim and Buttery Dick, the latter being among the most famous of Magdalen cats, and having served as unofficial Senior Fellow for some years. Though likely allowed in College on the proposal that a cat would control the vermin, Buttery Dick seems not to have done much such work, and to have been a terribly spoiled cat. He took his meals beside the President at High Table, and was seen by the Fellows to have rather sharp opinions of the cook’s creations.