It is possible to trace the development of Magdalen College’s main site through the multitude of depictions of Oxford, starting in the late 16th century. The layout of the core of Magdalen – Cloisters, Chapel and Hall – has hardly changed since the Agas map of 1578. Every other part of the College site, though, has gone through substantial refurbishments, reconstructions, clearances, and redevelopments. The constant changing nature of the College’s large expanse of land outside of the city’s walls included the relocation and reconstruction of Magdalen College School (several times), lodgings and public houses on High Street, the erection of the Botanic Garden, New Building, St Swithun’s and Longwall Quad, and finally the Grove.

Reproduced by kind permission of Bodleian Libraries, Gough Maps Oxfordshire 2, whole map. Scale c.1: 2,500.

This map was drawn by Ralph Agas in 1578 and engraved by Augustine Rythe, the first map of Oxford. It is oriented with south to the top of the maps, depicting the streets and buildings of the city pictorially – High Street runs from left to right with St Mary’s Church at the centre. Lower centre are the Divinity School and the University Schools – now part of the Old Bodleian. At lower right can be seen the city wall with the North Gate just visible at the right and at centre left Magdalen can be seen just outside the East Gate.

Detail of David Loggan’s map of Oxford from his Nova & accuratissima celeberrimæ universitatis civitatisque Oxoniensis Scenographia (1675)

David Loggan’s map of Oxford, found at the front of his Oxonia illustrata (1675), depicts the town with the north to the bottom, much like the Agas map above. By the end of the 17th century, Magdalen’s land had seen significant development: the addition of decorative gardens and a bowling green north of Cloisters, the reconstruction of many of the Magdalen College School buildings, and, most significantly, the newly-created Physic (now Botanic) Garden.

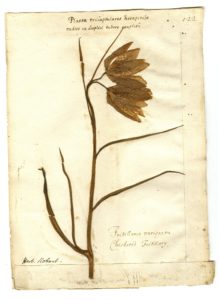

Fritillaria meleagris, this species was recorded as growing in the Garden in 1648. Oxford University Herbaria, Department of Plant Sciences BJr-03-122.

Every April, Magdalen’s Water Meadow is transformed into a sea of purple and white fritillaries. The blooming of these flowers brings crowds to College to see these flowers which were recently voted the county flower of Oxfordshire. Although commonly sold as an ornamental spring bulb, wild populations of fritillaries are rare. This is because their natural habits are unploughed meadows that are waterlogged during winter. Fortunately, Magdalen’s Water Meadow has been left largely untouched for centuries, providing an ideal habitat for these plants to grow in. For such an iconic flower with such a strong association to Magdalen, it may seem surprising that their origin in College still remains a mystery.

The debate about the Magdalen fritillaries can be split into two questions: Is the Magdalen fritillary population truly native? If it is not native, where did it originate?

Botanists still debate if fritillaries are truly native to the British Isles, or merely a garden escape. However, in the case of Magdalen it appears that the evidence is consistent with them being the latter. In 1794, in Flora Oxoniensis, the third Sherardian Professor of Botany was the first to describe fritillaries growing in the Magdalen grounds. What is surprising is that this observation was not made earlier. The absence of descriptions of fritillaries from the works of the eminent 17th century botanists with ties to Magdalen and the Botanic Garden makes it highly improbable that the plants were here and just simply overlooked. Instead, it is likely that Magdalen’s population of fritillaries are in fact garden escapees that only colonised the Magdalen grounds in the 18th century.

So if the Magdalen fritillaries are not native where did they originate? Although impossible to know for certain, Magdalen’s close links with the Botanic Garden may well hold the answer. What we know for certain is that fritillaries, both the characteristic chequered and white varieties common in the Water Meadow today, were being grown in the Botanic Garden as early as 1648. It is certainly within the realm of probability that they may have escaped the Botanic Garden to the Magdalen grounds.

However, the story of the fritillaries can potentially be traced even further back, a link identified by the current Vice President of Magdalen, and member of the Plant Sciences department, Professor Andrew Smith. When the 1st Earl of Danby decided to set up the Botanic (“Physic”) Garden in the early 17th century he had planned for John Tradescant the Elder (gardener to King Charles I) to be its first superintendent. Unfortunately, Tradescant died before taking up the post but had already helped provide plants for the Garden – and may have provided the fritillaries.

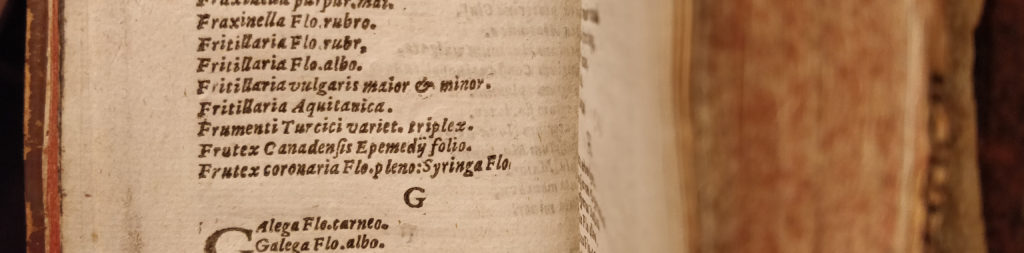

Detail of Plantarum in horto Johannem Tradescanti nascentium catalogus, 1634 (Magdalen College, Arch. B.II.1.19(2))

We know for certain that Tradescant was already growing fritillaries as is documented in his 1634 catalogue of his own gardens, the only known surviving copy of which is held here in the Goodyer Collection in Magdalen. It may well be that the fritillaries that transform the Water Meadow each year in fact have their origin tied to the foundation of the Botanic Garden and its proposed first superintendent, John Tradescant the Elder.

Even the trials of the Second World War did not induce the Fellows of Magdalen to neglect their ornamental animals. Ducks, swans, and other water fowl are a common sight throughout the College’s waterways, but the Duckery, a small pond at the far end of the Water Meadow, and its attendant duck house, seems to have been installed to entice these free-roaming wild birds to take up permanent residence in the College gardens.

This hand-drawn map, submitted to the Grounds Committee in 1941 depicts the Duckery by name, together with a register of the various trees in the meadow, and the shape of Addison’s Walk at the time. Though the Duckery and duck house remain well known to the ducks still in residence, this name seems to have fallen out of general use amongst College members.

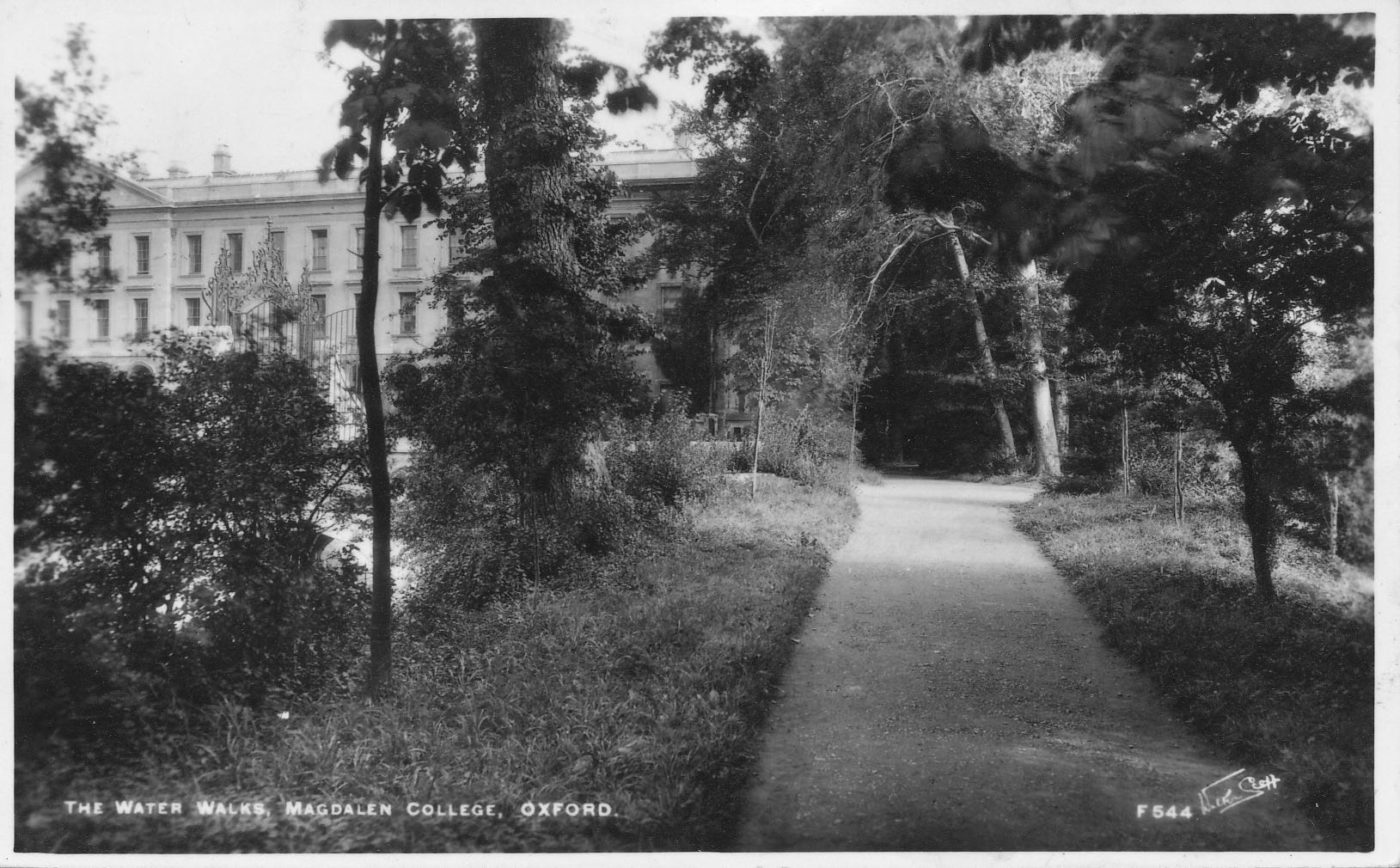

The area bounded by the splitting of the Cherwell to the east of College’s main site, Water Meadow, has long been a place of biological and geological curiosity. However, it, too, has acted as a gravity well for the creative minds of Magdalen, attracting some of College’s most noteworthy Fellows and Old Members. Originally labelled as ‘Water Walk’ and visible on early maps of Oxford, the College changed the name of the circular path around Water Meadow to ‘Addison’s Walk’ in the 19th century.

The essayist, poet and playwright Joseph Addison was elected a Fellow of Magdalen in 1698. He remained at Magdalen until 1711, during which time he established the magazines Tatler and The Spectator, both of which he contributed regularly. Addison made his first attempt at drama by contributing the libretto to Thomas Clayton’s opera Rosamond (1707), which was disastrously reviewed. He found later success with his Cato (1713) and The Drummer (1716).

It was in Oxford, though, that Addison’s delight in walking developed, which would be a life-long source of inspiration for the author. The wooded path then called ‘Water Walk’ was part of his regular circuit during his time at Magdalen, and it was renamed in his honour in the mid-19th century.

C.S. Lewis in his rooms at Magdalen College

Clive Staples Lewis was elected a Fellow and Tutor in English at Magdalen in 1925; a position he held for almost three decades. C.S. Lewis is perhaps most popularly known for his works of fiction such as The Chronciles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters, however he was also a prolific academic author and tutor to generations of Magdalen scholars, including John Betjeman.

Addison’s Walk was the site of a turning point in Lewis’s life, which he memorialised in his poem ‘Chanson d’Aventure’ (1938). It was here that in 1931 Lewis and his friends J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson took a walk in the early hours after midnight, the three having filled their evening with discussion around their lifelong fascination with myths. It was this discussion, and walk, and further conversations that eventually crystallized Lewis’s intention to convert to Christianity.

The Magdalen Plane on the lawns of New Building was planted in 1801 by Henry Philpotts, a Fellow of the College and later Bishop of Exeter. At its last measurement the tree was close to 100 ft high and had a girth of 25 ft. The plaque at its base said it is believed to be from the hybrid plane (now commonly called the “London plane”) first produced in the Botanic Garden in 1666. Although no record of a hybrid London plane is recorded in the Botanic Garden when it was catalogued in 1676, it is interesting that both parent species; Platanus occidentalis L. and Platanus orientalis L were being grown there.

For as long as Magdalen has had grounds to keep, there have been groundskeepers and gardeners to keep them. Early records unfortunately do not reveal who the first gardeners were; but our earliest accounts record salaries paid and materials purchased for the upkeep of Magdalen’s growing landscape.

Detail from “The Oxford Almanack for the year 1789” – the earliest depiction of gardeners hard at work in Magdalen. Here, they are cutting back a large tree which was obstructing what is now the Old Practice Room.

Early depictions of the College tell us a great deal about the plantings in familiar spaces – engravings and maps of the College from the 17th century show formal and decorative gardens in what is now the Grove, and plantings in Cloisters not dissimilar to what can be found today. Photographs from the 19th and early 20th century show much of College’s gothic buildings covered in ivy, and if you look close you can still see the scars of some of the roots on exposed stonework.

Gardening in Oxford colleges has seen significant professionalisation in the past century; all qualified gardeners will now have completed a two year City and Guilds course in horticulture, and many others will also have qualifications and training in more advanced activities like chainsaw usage, safe use of pesticides, or animal husbandry.

Portrait of Claire Shepherd, Head Gardener of Magdalen College © Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert, 2018

Magdalen’s Head Gardener, Claire Shepherd came to Magdalen as the apprentice back in 1986. “I trained at Waterperry Gardens where I completed a two year City and Guilds course in Amenity Horticulture,” Claire said in a recent interview. “Later on I completed my NVQ Level 3 then a course in management and other training including the use of chainsaws and the safe use of pesticides.” When asked about working as a Head Gardener at Magdalen, Claire said that “Magdalen is very unique. We need to have a wide selection of skills as well as horticulture. One day we could be dealing with deer, one day mowing the lawns and another repairing paths. In all the 30 years I have been here, my job has never been boring or dull. There is always something that needs doing normally the work load out ways the work force!”

“My favourite part of the job is working in an amazing environment, such beautiful surroundings. I feel privileged that I am responsible for looking after the gardens and grounds. My least favourite things are sitting in front of a computer screen when I could be outside!”